January Reset: Rebuilding Belonging, Routines, & Reasoning in the Math Classroom

If you've taught middle school math, you know the winter break pattern. Students return restless, ready to test the class boundaries, and seeming to forget all the routines that were second nature in November. On the flip side, we feel the pressure to "get back on track" immediately, ready to push through content to make up for lost time. As a result, frustration builds and discipline referrals spike. And underneath it all, everyone, students and teachers alike, is wondering the same thing: Why am I here?

Here's what research and classroom reality both confirm: January is not a continuation of December. It's a reset. And the most savvy math teachers treat it that way. They don't pretend students will walk in ready to pick up exactly where they left off. They plan for re-entry with the same intentionality they bring to the first week of school. They know that belonging must be rebuilt, routines must be reestablished, and reasoning capacity must be reactivated before academic momentum can return.

This isn't about lowering expectations or wasting time on fluff activities. It's about understanding how learning, memory, and community work; then designing instruction that accounts for what students actually need after a break, not what we wish they needed. This post gives you a framework for navigating the December-January transition with both your culture and content intact. Whether you're a teacher planning your next unit or a building leader supporting your math team, these strategies will help you turn January from “a month of catching up” into “a month of building forward.”

Avoiding The December-January Instructional Trap

Part 1: Why Rushing Before Break Backfires

Let's name what happens in nearly every middle school in December. Math teachers look at their pacing guides, realize they're "behind," and make a fateful decision: We have to finish this unit before break. So they rush. They cut discussion time. They assign more practice and less sense-making. They push through the last few lessons at breakneck speed, hoping students will "get it" by the time winter break arrives. And then, inevitably, students return in January having forgotten most of what was crammed in during those final frantic weeks.

The truth is this instructional trap isn't a time management problem. It's a fundamental misunderstanding of how students learn. When teachers rush to finish a unit before a long break, they're working directly against what we know about memory consolidation and cognitive load. Students need time and repetition to move new learning from working memory into long-term memory. They need opportunities to practice, make errors, receive feedback, and revise their thinking. Cramming complex procedures into the last week before break, when students are already emotionally and cognitively depleted, virtually guarantees that learning won't stick.

Zaretta Hammond describes this phenomenon in her book Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain. The brain needs time to consolidate learning and create strong neural pathways. When we rush through content without allowing time for processing and practice, we're essentially asking students to build on quicksand. Students may demonstrate understanding in the moment, but without adequate consolidation time, that understanding will evaporate over break.

Here are some example:

If you're teaching ratios, don't introduce multi-step ratio problems or complex unit conversions in the final week before break.

If you're teaching percent applications, don't introduce percent increase/decrease, tax, tip, and discount problems all at once in the final week.

If you're teaching linear functions, don't introduce writing equations from two points right before break.

Notice the pattern? These are all high-cognitive-load procedures that require accuracy, multi-step abstract thinking, and procedural fluency. They're exactly the kind of content that students will struggle to recall after two weeks away.

The most efficient math departments intentionally sequence content so January re-entry is easy for them, AND for students. They plan in advance to end December on anchor ideas. These are the big concepts and representations that students can reactivate quickly when they return. Good stopping points are places where students are drawing representations of problems, acting out word problem situations, or using manipulatives to explore mathematical relationships.

A better idea is to:

End on representations: If you're teaching operations with fractions, end with students using area models or number lines to represent fraction multiplication. Save teaching the algorithm for when students return.

End on conceptual understanding: If you're teaching integers, end with students exploring what negative numbers mean in real-world contexts (debt, temperature, elevation) and representing them on number lines. Save teaching integer operation rules for January when you can dedicate proper time to sense-making.

End on exploration and noticing: If you're teaching proportional relationships, end with students noticing what stays the same and what’s different between representations of proportional and additive relationships. Save the formal equation-writing for after break.

When you end on an anchor idea, you give students something memorable to hold onto. Visual models are easier to recall than procedures, conceptual understanding provides a foundation you can build on, and when students return, you can say, "Remember when we were working with [insert concept] before break? Let's start there again today," and students can reactivate that prior knowledge in under 10 minutes. This approach doesn't slow you down. It positions you for faster progress in January because you're building on solid ground instead of reteaching from scratch.

Part 2: Why Discipline Spikes After Break (And Why It's Not Defiance)

Now we need to discuss the real time barrier: student behavior. If you've noticed that the first week back from winter break feels similar to the week before break, you're correct. Discipline referrals consistently spike in the days immediately following long breaks. What's critical to understand is that while this feels like defiance, it's really students testing whether they still belong.

Brown and Seda explain in Choosing to See: A Framework for Equity in the Math Classroom that students who test limits might be trying to answer: “Does my teacher still see me? Do the rules still apply to me the same way they did before? Am I still safe here?” Students (especially those who've experienced instability, trauma, or marginalization) need to know that the classroom community they were part of in December still exists in January. Testing boundaries is how they check.

This is particularly true for middle schoolers, who are developmentally navigating questions of identity and belonging. Winter break disrupts the daily rhythm and relational predictability that help students feel secure. Two weeks away from school means two weeks away from the peer connections, adult relationships, and structured routines that anchor them. When they return, they're not just academically rusty, they're relationally uncertain.

Teachers often feel guilty, embarrassed, or frustrated when misbehavior increases after break. They wonder, What did I do wrong? Why can't they just remember how we do things here? Let's reframe this: The post-break misbehavior spike is not a reflection of your teaching or classroom management. It's a predictable response to disrupted routine and community. Understanding this distinction changes everything and helps you to shift your response from punitive to restorative.

In no way am I advocating that you ignore misbehavior or lower expectations. In fact that is the worst thing you could do. I am advocating for you to respond to student behavior with strategies that rebuild trust and community, rather than simply tighten control. To do so, you must understand that the student who's pushing back on directions isn't necessarily challenging your authority, they might be checking whether you will still respond with the same consistency and care that you showed in December.

Part 3: Using Routines to Rebuild Belonging and Reasoning

When students return after winter break, you don't have to choose between addressing behavior and teaching math content. In fact, the same instructional moves that rebuild classroom belonging can also reactivate student reasoning. High-yield routines aren't just warm-ups or time-fillers. They're community-building tools that signal how students should engage in mathematics.

For example:

Let's say you return from break and need to reactivate students thinking about number notation and mathematical symbols. Here's what a 10-minute structured routine might sound like:

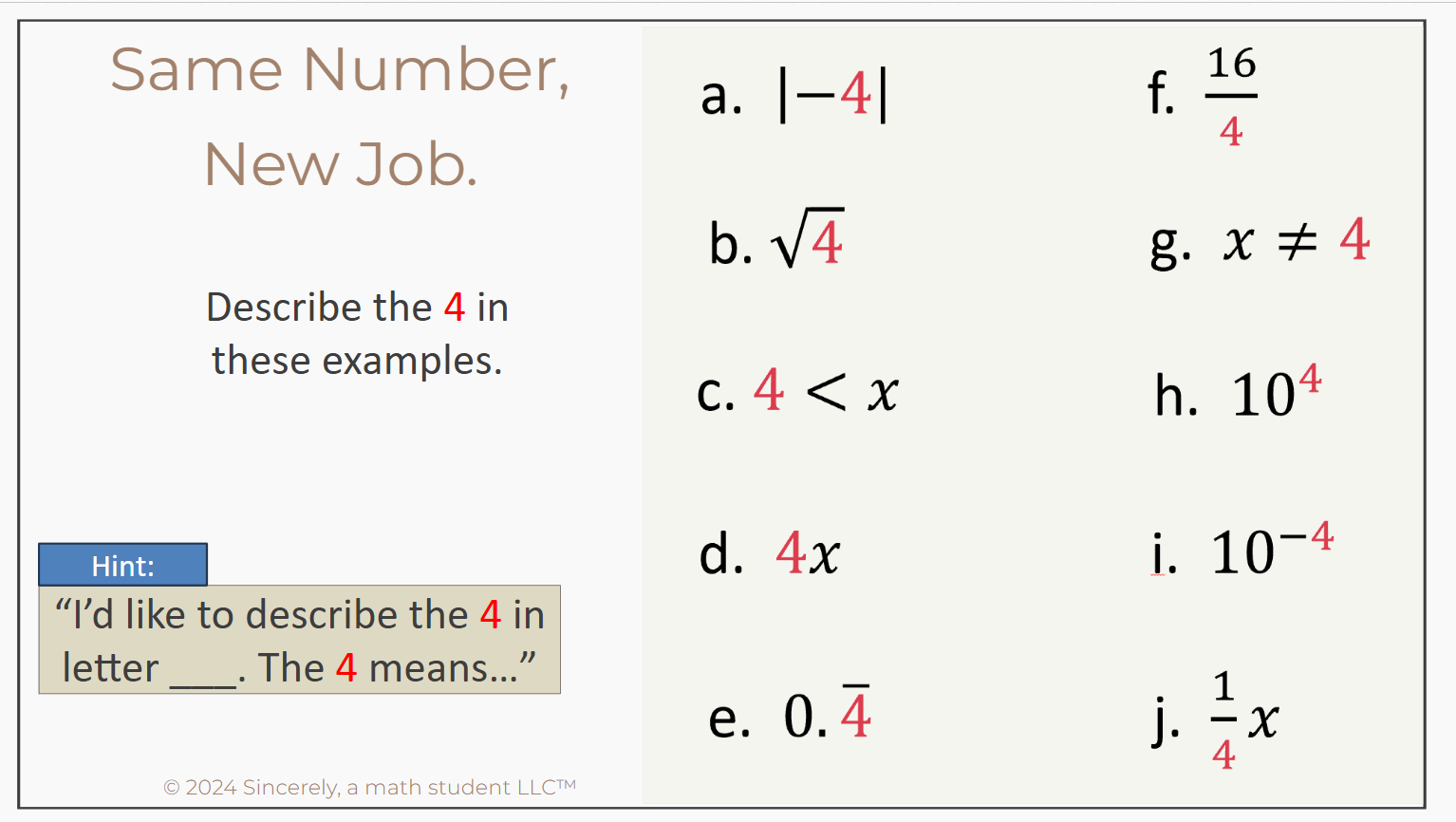

Teacher: "Welcome back! We're going to start with a routine called Same Number, New Job. I'm going to display examples where the number 4 shows up, but it has a different job in each example. Your task is to describe what the 4 means in each case."

[Display the image with examples a–j showing 4 in different contexts.]

Same Number, New Job Reasoning Routine

Teacher: "Take 30 seconds of silent think time. Pick one example and figure out how you'd describe the 4 in that example. Use the sentence starter to help you."

[Pause for think time.]

Teacher: "Now turn to your shoulder partner. Each of you take turns sharing one example you picked. You have two minutes."

[Students talk. Teacher circulates, listening for how students are describing the different roles of 4. Consider letting students share about 3-4 times.]

Teacher: "Let's hear from a few groups. Who wants to share? Marcus, which example did you and Nia discuss?"

Marcus: "We talked about letter d. The 4 means you have four groups of x."

Teacher: "Nice. So the 4 is telling you how many x's. Did anyone pick a different example? Sophia?"

Sophia: "We did letter a. The 4 is negative four, but the absolute value makes it positive, so the 4 means the distance from zero."

Teacher: "I love that you're thinking about what the 4 represents, not just what the answer is. That's exactly the kind of thinking we'll keep practicing this month."

As students get comfortable with this routine, you can ask more rigorous questions like:

"Select two examples that are the same. How did you decide?"

(This pushes students to identify equivalent forms or underlying structure.)"Which of these examples represent integers? How did you decide?"

(This requires students to classify and justify.)"Which of these examples are opposites? How did you decide?"

(This activates thinking about inverse relationships.)

Notice that each question ends with "How did you decide?" This is intentional. You're not just asking students to identify correct answers, you're priming their thinking for jumping back into content by allowing them to practice explaining their reasoning.

What this routine accomplishes in 10 minutes:

It reestablishes predictability. Students remember, "Oh right, this is how math class works here."

It positions all students as mathematical thinkers. There are multiple valid observations to make, not one right answer.

It creates low-stakes opportunities for participation. Students can start with an easier example and build confidence.

It rebuilds relational connections. Partner talk reminds students they're part of a learning community.

It reactivates prior knowledge. The teacher can hear what students remember about integers, exponents, fractions, and more; all in one routine.

It builds the habit of making, testing, and evaluating mathematical statements. This is a skill students rarely get time to practice, but that's essential for deeper reasoning.

How Leaders Can Support Teachers Through the December-January Trap

Teachers don't need more initiatives in January. They need affirmation, clarity, and protected time. If you're a building leader, here are three high-leverage moves that ease overwhelm instead of adding pressure:

1. Affirm What Worked Before Break

Before jumping into improvement conversations, ground your teachers in success. Use a data talk protocol that forces teachers to examine student mastery from the fall semester and ask, "What do you think contributed to such high levels of success? How can we replicate that?"

This isn't about ignoring areas for growth, it's about anchoring growth conversations in what's already working. When teachers can name their strengths, they have a foundation to build on rather than feeling like they're starting from scratch. This approach builds teacher confidence and reduces the defensive posture that often accompanies feedback conversations.

2. Pre-Plan January Re-Entry Routines With Teachers

Use team meeting time or schedule a short planning session before winter break (or in the first days back) where your math team discusses:

What reasoning routine will we use in the first week back?

What anchor concept from December can we reactivate quickly?

What behavioral expectations will we explicitly re-teach?

When teachers plan together, they're less likely to feel isolated during the post-break chaos, and a shared plan means students experience more consistency across classrooms.

3. Protect Planning Time

If initiatives are consuming your teachers' planning periods, January is the time to take a pause so they can find their footing. Ask, "How does this meeting support my teachers' ability to plan re-entry instruction that rebuilds student reasoning and belonging?" If the answer isn't clear, advocate for postponing non-essential meetings until February. Your teachers need time to think, plan, and collaborate. Protecting that time is one of the most consequential leadership moves you can make.

Moving Forward

January doesn't have to be a month of catching up, surviving, or white-knuckling through behavioral chaos. It can be a month of resetting with intention, rebuilding the routines and relationships that make great math instruction possible, and reactivating student reasoning in ways that feel manageable for teachers and meaningful for students. This requires a mindset shift. Instead of treating January as a continuation of December, treat it as a fresh start. Instead of rushing back into content, invest time in re-entry activities that support content mastery and positive behavior.

When you make these shifts, January becomes less overwhelming. Teachers feel more grounded and students feel more connected, and the academic momentum we are all hoping for actually builds because it's rooted in the conditions that make learning brain friendly.

Your Next Step: The Math Feedback Reset Strategy Session

If you're a school-based Administrator or Instructional Coach reading this and thinking, This makes sense, but I need help bringing it to life in my building, I want to invite you to explore the Math Feedback Reset Strategy Session.

This session is designed specifically for leaders who want to support their math teachers through the January transition without adding to their overwhelm. We'll work together to:

Audit your current observation and feedback practices to identify what's working and what's creating unintentional stress

Design affirming learning walk protocols that build teacher confidence while maintaining high instructional expectations

Create a plan that aligns your department around routines, behavioral expectations, and reasoning-focused instruction

Develop a sustainable feedback cycle that prioritizes replication of success, not just identification of deficits

The goal isn't to add another initiative to your plate. It's to help you refine the systems you already have so they support teachers more effectively.

January is coming. Let's make it a reset, not a setback.

Ready to explore whether this is the right fit for your team?

What strategies have worked in your building for navigating the December-January transition?

Drop a comment below or reach out. I'd love to hear what's resonating with your math team.